RECETTO, Italy — For six days in northern Italy, water skiing seemed determined to burst out of its own history. The 2025 World Championships were not just a contest for medals but a collision of eras: champions fighting to defend their crowns, teenagers breaking through the gates, and performances that stretched the sport into new territory.

It didn’t start that way. The opening days were reshuffled by storms, rain smearing across the placid waters of Recetto. But by Friday the skies cleared, the wind fell flat, and the lake turned to stillness. What followed was a rush of personal bests — especially in jump, where skiers pushed themselves farther than anyone thought possible.

The Prelims: Cracks in the Armor

Joel Poland walked down the dock on Friday with the casual confidence of a man who had won everything there was to win. Tricks has always been his insurance policy in overall, the foundation of his dominance. And yet, in a mirror of his stumble at the last Worlds, he went down early.

“That was just heartbreaking,” Poland admitted later, frustration in his voice. “Like a dream… gone, again.”

The mistake rattled the field. Pato Font and Mati Gonzalez wobbled through their passes. The cut line fell to its lowest in nearly a decade — not from weakness, but nerves. Suddenly, the men’s trick final looked wide open.

On the women’s side, it was the opposite. Regina Jaquess and Jaimee Bull tore through 10.75m (39.5′ off) with machine precision, while 22-year-old Kennedy Hansen quietly put together personal bests in both slalom and jump. By the end of Friday, she was in the mix for overall medals — and a genuine threat to Hanna Straltsova’s iron hold on the crown.

Saturday Fireworks

By Saturday the tournament had caught fire.

Men’s slalom provided the starkest reminder of how far the sport has evolved. For the first time in history, a piece of three at 10.25m wasn’t enough to guarantee a finals spot. Twelve skiers, all within a buoy of one another, crammed the leaderboard. Even Poland, hoping to rebound, was squeezed out with 2.25 at the pass.

Tricks went ballistic: seven women cracked 9,000, with Erika Lang and Neilly Ross punching past 11,000 for the first time ever at Worlds. “It’s hard in prelims — you just want to secure your spot,” Ross said afterward. “Hopefully tomorrow I can just go and go fully.”

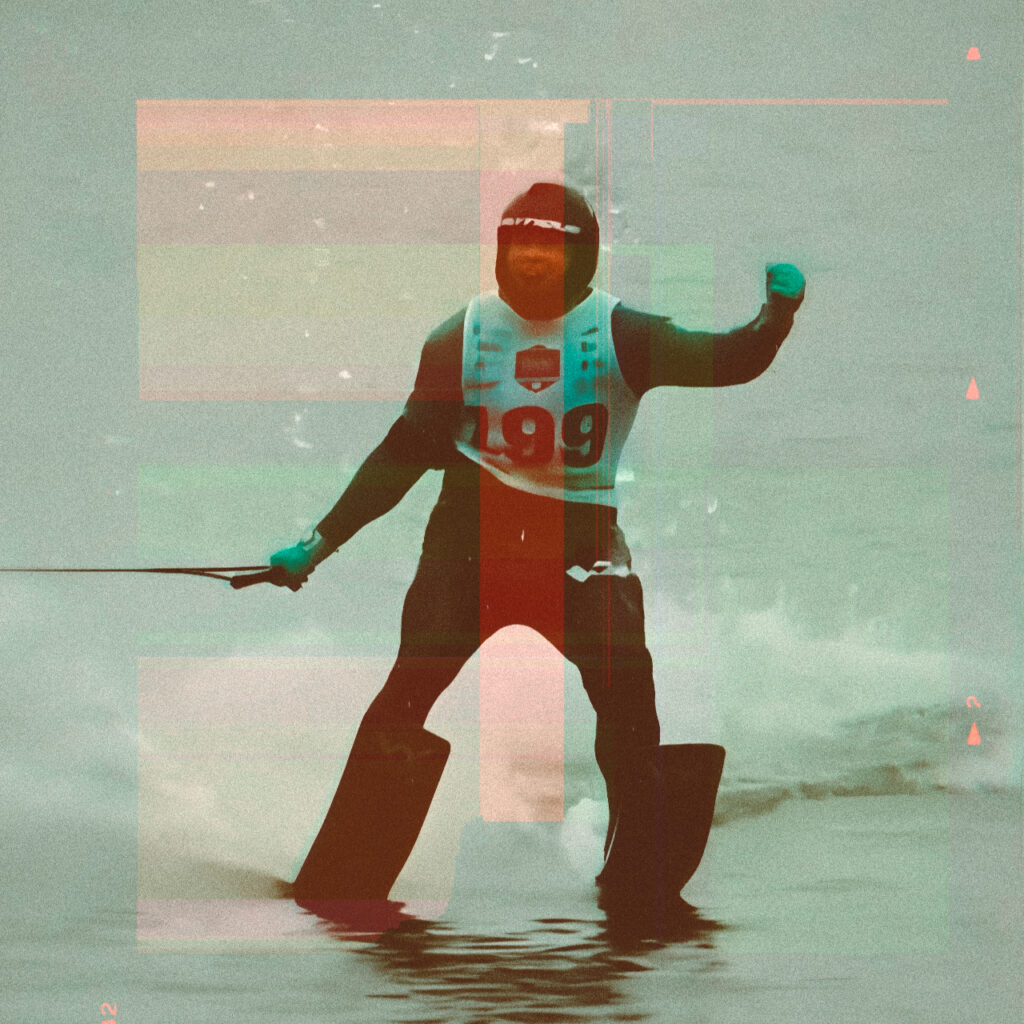

And then came men’s jump. Dorien Llewellyn, after three years battling injury and inconsistency, soared 69.6m (228 feet) — his longest since 2021. The leap pushed him into the overall lead, just 13 points clear of Louis Duplan-Fribourg, setting up the tightest overall showdown in recent memory.

Ryan Dodd and Poland tied for the lead at 70.5m (231′), a strange echo of their summer duel at the California ProAm. Everywhere you looked, it felt as if the old guard and the new blood were destined to collide.

Finals Sunday: A Collision of Eras

By Sunday the tournament had shed its nerves. The storms were gone, the prelim jitters gone. The water in Recetto lay flat, as if it knew history was waiting.

Tricks: Margins Measured in Frames

Tricks is the cruelest event because immortality and anonymity can hinge on a single freeze-frame. For decades, only the judges saw those margins. This time, thanks to EyeTrick, everyone did. Fans could watch a world title swing on whether a toe slide was rotated 90 degrees or 85.

The women’s final was billed as a heavyweight clash: Lang’s innovation, Ross’s precision, Anna Gay Hunter’s pedigree. But the first half of the field faltered, pressing too hard on risky runs. Hunter steadied things with 10,730, matching her prelims to lock in a medal. Lang went next, laying down a world record run, but missed the rope on her ski-line back-to-back. Three hundred points vanished in an instant.

That left Ross. At 24, she has often played second fiddle to the older Lang or Hunter. But in the past year has found another gear. Two immaculate passes later, the scoreboard confirmed what her posture already said: World Champion.

“I haven’t won a Worlds since 2017,” Ross said, shaking her head. “Every single one since then I’ve just kinda blown it. We made this the goal — do my run. Today I just went for it. I really wanted this one.”

The men’s event spiraled into chaos. Defending champion Font posted 12,010. Then Gonzalez — all velocity and audacity — strung together a blistering 5,500-point toe run, backing it with a clean hand pass for 12,410. It forced the rest into desperation.

Llewellyn, trying to put the overall race out of reach, sank in disbelief after a miscued landing. Abelson, the wunderkind and world record holder, seemed composed — until the scoring system caught him. A rushed toe slide, four judges ruling it under-rotated, pushed his buzzer beating toe-line-front out of time. His final total: 12,400. Ten points short.

Ten points. The smallest possible increment in trick skiing. The kind of number that sticks forever.

When Duplan-Fribourg couldn’t repeat his prelim magic, Gonzalez was champion — speechless on the dock. “It feels amazing,” he stammered. “It was my dream… now I can say I did it. Congrats to Jake too — he’s one of the best in the world. We have the best here.”

Slalom: The Old Guard Meets the Future

Women’s slalom opened with an unlikely spark. Sade Ferguson, once a junior jump prodigy until injuries derailed her career, returned as if she’d never missed a season. Her 5 @ 10.75m was a huge personal best and an early lead.

Allie Nicholson scraped half a buoy past it. Jaimee Bull, calm as a metronome, became the first to run 10.75, but faltered at 10.25 with a botched S-turn for just one and a half. Regina Jaquess, chasing history, fought through 10.75 off but couldn’t get her ski outside of two at 10.25. The shoreline knew instantly what it meant: Bull, 25 years old, three straight World titles.

“I can’t really believe three in a row,” Bull said. “Two felt crazy. Today I didn’t think that was enough — but it was.”

The men’s final felt like two different sports at once: veterans clinging to relevance and a new generation kicking the door down. Freddie Winter bowed out early. Will Asher, seemingly reborn, posted five at 10.25 and celebrated like a man half his age. Then Nate Smith made 10.25 look like a warm-up, forcing the others to gamble.

One by one they failed — until Charlie Ross, 20 and fresh off his first pro wins, matched Smith. He ran 10.25 smoother than anyone, tying at 9.75 to force the runoff. Smith, the most reliable closer the sport has ever known, prevailed. But Ross walked away with proof he belonged in the deepest end of the pool.

“I’ve never even tried 41 off the dock in practice,” Smith admitted afterward. “At two, a lot goes through your head — should I stand up, should I turn it? But today, yeah… I’m pretty happy. That’s cool.”

Jump: Shaved Heads and Broken Dynasties

Jump was the crescendo, the shoreline swelling with every flight. The women’s final opened with personal bests — Maise Jacobsen, Aaliyah Yoong Hannifah both cracking 50 meters — before Brittany Greenwood Wharton, back from injury, hit 54.4m (178 feet), her longest in years. Straltsova needed only two jumps to secure the crown and her golden double. “I’m so happy,” she said simply. “It’s hard to defend.”

The men’s jump final had more plotlines than an HBO drama. Tim Wild, just 18, came off the lower ramp and went 68.1m — ten days earlier he’d never cracked 60. Bronze overall, his name now etched into the sport’s future. Duplan-Fribourg faltered in his overall defense, leaving Llewellyn to claim the title he’d chased for years.

But the jump crown itself belonged to Poland. His opening leap — 72.1m, the biggest of his life and a new European record — stopped the shoreline in its tracks. He passed his next two, gambling it would hold. It did.

Ryan Dodd, five-time champion, threw everything he had, cracked 70, but fell short. With that, three decades of North American dominance — Krueger, Jaret, Dodd — ended. Poland’s elation as he hit the water carried something more than victory. It carried release.

“Yeah, that was unreal,” he said, still buzzing. “This shaved head… I might have to keep it. It seems to be working. Over the moon.”

A New Benchmark for the World Championships

In the end, the numbers told the story. Recetto didn’t just host a World Championships — it redefined what one looks like. The cut to make the finals in men’s slalom, men’s jump, and women’s tricks was the highest in history, a staggering testament to the depth of talent on display. Tournament records fell or were matched in women’s tricks, men’s slalom, and women’s slalom, while the podiums in both men’s and women’s slalom and tricks went down as the four highest-scoring in the sport’s history.

The pattern extended across every discipline. The men’s jump final produced the second-highest podium ever, as did the men’s overall — each pushed to the brink by athletes refusing to give an inch. And beyond the headlines and record books came the quieter triumphs: the countless personal bests, the season-best performances, the moments where skiers left the dock knowing they had just redefined their own ceiling.

That’s what made Recetto different. This wasn’t simply another Worlds where one or two stars lifted the level. It was a collective surge, a field-wide elevation that left even veterans shaking their heads. When the dust settles, 2025 may well be remembered as the World Championships where water skiing itself moved to the next level.