Year in review: We countdown the most memorable moments of the 2025 water ski season

The moments that defined the 2025 water ski season – and the stories behind them.

By Jack Burden

Water skiing in 2025 was a year of rising performances and expanding possibility. Records fell, ceilings collapsed, and moments that once felt unimaginable became routine. From teenagers rewriting history to veterans redefining resilience, the season delivered a relentless stream of storylines that pushed the sport forward while constantly testing its limits. It was a year where brilliance arrived in waves, controversies lingered, and the level required to win climbed higher with every event.

Across the Waterski Pro Tour, WWS Overall Tour, IWWF world championships at every level, and legacy stages like Moomba and the U.S. Masters, the sport unfolded through breakthroughs, confrontations, and generational shifts. New rivalries ignited. Established orders were challenged. And in disciplines once thought to have plateaued, sudden surges forced a rethink of what elite performance truly means.

As we count down the most memorable moments of the 2025 season, this list captures more than just victories and records. It reflects a sport in full acceleration—deeper, bolder, and more competitive than ever—and the athletes who defined it when expectations were highest and the spotlight brightest.

Image: Joshua Devenie

10. Austria Takes Auckland

There’s always a particular optimism baked into the first major tournament of the season. The days grow longer, boats are dewinterized, and spring fever sets in. In recent years, that role has belonged to Moomba. But in 2025, the season’s opening statement came a week earlier—and from an unexpected corner of the calendar.

The University World Championships returned for the first time since 2016, staged in Auckland’s Orakei Basin, salt water shimmering in the heart of the city. The “Collegiate Worlds” brought together student-athletes from five continents, blending future stars, established pros, and wide-eyed newcomers thrilled to wear national colors. There were personal bests everywhere. There was Aaliyah Yoong Hannifah making history. And then there was Austria.

What the four Austrians pulled off bordered on absurd.

Against a Team USA contingent 14 strong—including a stacked six-skier A-team—Austria arrived with just four athletes. One was a single-event skier. Another, their strongest overall threat, withdrew at the last minute. There were no alternates. No safety nets. In tricks and jump, one misstep would have ended everything.

Instead, every skier delivered.

Luca Rauchenwald won jump outright. Lili Steiner claimed silver in jump and overall. Nikolaus Attensam posted the top men’s slalom score of prelims, maximizing team points. And Dominic Kuhn’s bronze in tricks—behind a field loaded with world champions—proved decisive.

In the 80-year history of IWWF world championships, only six nations had ever finished ahead of the United States. Only five had ever won a team title.

Make it six.

Undermanned, unflinching, and utterly fearless, Austria didn’t just win Auckland—they announced themselves. And in doing so, gave the 2025 season its first unforgettable moment.

Image: Johnny Hayward

9. The Race to 13k

There was a time when 13,000 points in men’s trick skiing felt like a myth. A ceiling. A number whispered with admiration, then dismissed with realism.

Enter Jake Abelson.

On a hot June weekend at Ski Fluid in central Florida, the 17-year-old American became the first skier in history to cross the barrier, posting 13,020 points. When the IWWF ratified the score, it didn’t just crown a new world record holder—it confirmed that trick skiing had entered a new era.

The milestone was years in the making. For nearly two decades, progress at the elite end of men’s tricks had been incremental, almost stagnant. Then came a surge. Patricio Font reignited the discipline in 2022. Matias Gonzalez raised the ceiling with relentless speed and precision. Suddenly, 12,000-point runs weren’t exceptional—they were the price of admission. In 2025, every men’s professional trick event was won with a score north of 12K.

The race to 13K was on.

Abelson got there first—but only just. Gonzalez and Font were right behind, pushing from different angles: Font with ruthless hand-pass efficiency, Gonzalez with audacious toe speed. And while Abelson claimed the milestone, the season’s most compelling moment came later.

At the World Championships in Recetto, with titles—not records—on the line, Gonzalez edged Abelson by ten points. Ten. The smallest possible margin in trick skiing. A single freeze-frame separating gold from silver.

In that sense, 13,000 wasn’t the finish line. It was proof of how narrow the margins have become.

The barrier fell. The chase went on.

Image: Bret Ellis

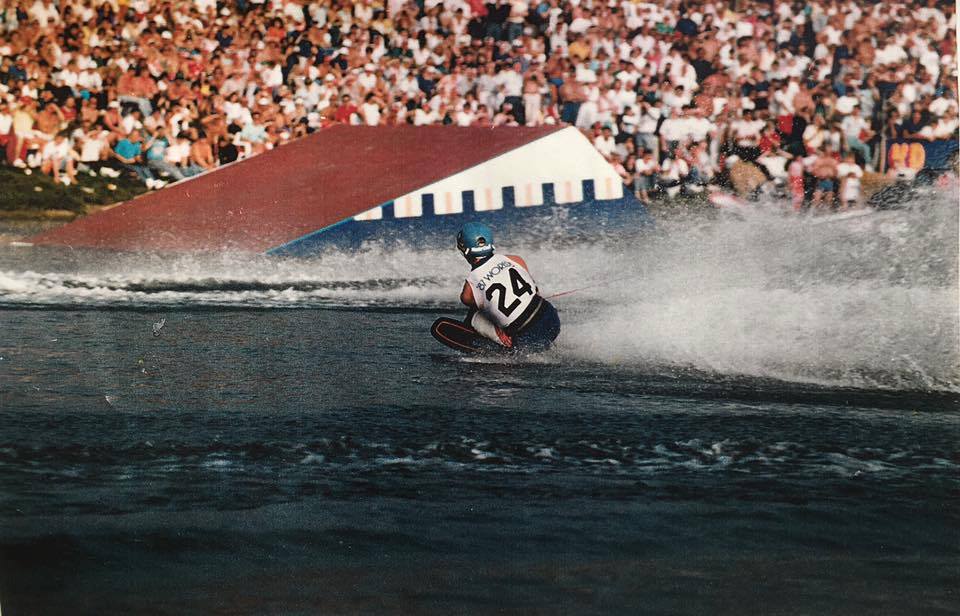

8. Travers Finale Shatters All Records

For decades, 10.25 meters—41 off—stood as men’s slalom’s final frontier. A pass reserved for the extraordinary, spoken about in reverent tones. By the time the sun set on the 2025 Travers Grand Prix, it felt like something else entirely: the new baseline.

At Sunset Lakes in Groveland, four different skiers ran 41 off a combined seven times, obliterating the previous record of four, set just two years earlier. It wasn’t an isolated spike, either. Across the back half of the season—World Championships, MasterCraft Pro, and now Travers—men’s titles have increasingly been decided at 9.75 meters (43 off). The ceiling didn’t just crack in 2025. It caved in.

Nate Smith and Charlie Ross had led the charge, but at the Grand Prix they were joined by Jonathan Travers and Freddie Winter, all four pushing through 41 and into rarified air. Winter went furthest when it mattered most, advancing to 43 and sealing both the event win and his first-ever Waterski Pro Tour season championship.

“This is the first season title I’ve ever won,” Winter said, emotion spilling over. “A year and a half ago I had a really terrible time, I hurt myself, and I worked really hard to come back… This one’s for everyone who helped me come back.”

The women matched the drama stride for stride. Regina Jaquess, Jaimee Bull, and Whitney McClintock Rini produced the first three-way tie at 41 off in waterski history, forcing a cold-start runoff at 10.75 meters. Jaquess prevailed on the water, but Bull walked away with the bigger prize—her fifth consecutive Pro Tour season title.

Seven 41s. Four skiers into 43. One unmistakable message: the sport’s limits are shifting, and fast.

Image: Johnny Hayward

7. Controversial Calls in Calgary

Unfortunately, one of the most memorable moments of the 2025 season earned its place in this countdown for all the wrong reasons. The Under-21 World Championships in Calgary were meant to spotlight the sport’s next generation. Instead, they became a reminder that, at times, judging—not skiing—can define a championship.

Held at Predator Bay, the U21 Worlds delivered much of what the event promises: breakout performances, record scores, and glimpses of future world champions. But during the women’s trick final, the focus shifted abruptly from athletic brilliance to adjudication.

When Colombia’s Daniela Verswyvel had her reverse mobe—an 800-point, title-swinging trick—ruled no-credit, the reaction was immediate and explosive. Live chats lit up. Elite skiers voiced disbelief. Formal protests were filed in the aftermath by Colombia, Canada, and the United States. The call stood, awarding gold to Canada’s Hannah Stopnicki and leaving Verswyvel heartbroken.

To her credit, Stopnicki—a deserving champion who could easily have won the title without controversy on another day—handled the moment with grace, embracing Verswyvel in a tearful scene that captured both the beauty and brutality of elite sport. “I know the judges are looking at everything extra carefully,” Stopnicki said afterward. “I was just trying to be as clean as I could be.”

The controversy didn’t end with the medals. The IWWF World Waterski Council launched a formal review, with Chief Judge Felipe Leal concluding—supported by EyeTrick data—that the panel was “very strict but consistent.” The issue, he stressed, was an unusually high number of non-credit calls that left many athletes dissatisfied.

The fallout reached beyond Calgary. Ahead of the Open Worlds in Italy, the Council committed to judge clinics aimed at improving consistency and restoring trust.

In a week meant to celebrate the future, Calgary instead exposed a fault line the sport can’t ignore. Trick judging, for all its tools and systems, remains far less objective than we’d like to believe.

Image: Moomba Masters

6. The Moomba That Launched a New Generation

The 64th Moomba Masters on Melbourne’s Yarra River wasn’t just another stop on the pro circuit—it was the crucible in which a new generation of champions was forged. Across the festival’s six professional events, four were won by first-time champions, setting the stage for breakthrough seasons.

In men’s tricks, 17-year-old Jake Abelson claimed his first professional victory, topping the highest-scoring podium in history. Moomba proved the launchpad for a meteoric season: Abelson went on to win the three largest prize-purse events, break the 13,000-point mark, and finish 2025 as the sport’s most dominant trick skier, despite a narrow World Championships defeat.

Slalom followed a similar trajectory. Nineteen-year-old Charlie Ross secured his first pro title with veteran composure, then rode that momentum to two pro wins, seven top-five finishes, U21 World Championships gold, and a silver at the Open Worlds—emerging as a genuine threat to Nate Smith and Freddie Winter for years to come.

The jump event crowned Joel Poland, returning from his Australian ban, as Moomba champion for the first time, launching an undefeated six-win season in men’s jump—a feat not achieved by any man since Freddy Krueger in 2006. Brittany Greenwood Wharton also claimed her debut professional victory, kicking off a season that included five podiums and a runner-up finish at the World Championships.

By the time the fireworks lit up Monday night’s jump finals, Moomba 2025 had delivered more than victories. Record-breaking performances, first-time champions, and a rising crop of elite athletes signaled a shift in the sport’s competitive landscape, reaffirming why the Moomba Masters remains water skiing’s ultimate proving ground.

Image: Johnny Hayward

5. Ross and Smith Runoff for the Crown

The 2025 World Championships delivered countless historic moments, but perhaps none more electrifying than the men’s slalom final in Recetto—a showdown that redefined what elite slalom looks like.

When Nate Smith, one of the most reliable closers in water skiing history, posted one at 9.75m (43 off) skiing fourth off the dock, it seemed the title was settled. But over an hour later, 20-year-old Charlie Ross left the dock and matched him—forcing a sudden-death runoff for the world championship. For the first time in World Championships history, two skiers had to attempt 10.25m (41 off) cold, with gold on the line.

It was a generational collision. Smith, the standard-bearer of modern slalom. Ross, the breakout force of the year. Smith prevailed in the runoff, but the result felt secondary to the message: the gap had closed.

“I’ve never even tried 41 off the dock in practice,” Smith admitted afterward. “A lot goes through your head… but yeah, I’m pretty happy.”

The drama didn’t end in Italy. Weeks later, at the very next pro slalom event, Ross and Smith found themselves locked together again—tied once more at 43 off. Another runoff. Another razor-thin separation. Different venue, same script.

Back-to-back ties at the hardest line length in the sport, across two of the biggest stages of the season, felt less like coincidence and more like a turning point. Smith still claimed the crown, but Ross had firmly announced himself as his equal.

In a season defined by record-breaking depth and shrinking margins, no moment captured water skiing’s new reality quite like this one: the champion tested, the challenger confirmed, and a rivalry forged buoy by buoy at 43 off.

Images: Thomas Gustafson

4. Lang vs. Ross Takes Tricking to the Next Level

If 2025 has a defining rivalry, it has to be Erika Lang versus Neilly Ross. Lang started the season seemingly untouchable, going undefeated across Moomba, Swiss Pro Tricks, and the Masters, reclaiming the world record from Ross, and setting the tone for a dominant year.

Ross, meanwhile, looked out of sorts early on, traveling the globe and honing her craft in a grueling schedule that included competing in the men’s field in Monaco. It took six pro events, but in Portugal she finally broke through, clinching her first win of the season and nearly matching world record form—a statement that she was back.

The rivalry erupted at Botaski. Lang set a pending world record in the prelims, only for Ross to tie the current record in the finals, forcing Lang to chase a second world record just to win. Every trick, every frame, every point counted. Ross’ victory marked her first major triumph in three years and signaled a shift: Lang’s dominance was no longer assured.

The drama carried into the World Championships in Recetto, where both women arrived in red-hot form. Once again, victory was decided by a hair’s breadth, with Ross’ late-season momentum peaking at the perfect moment. Two athletes, pushing the limits of skill and precision, raised the standard for women’s trick skiing, making every pass a spectacle and every point a headline.

Lang remains one of the most successful women in the modern era, but Ross has proven she can match, and even surpass, the best—turning a personal comeback into one of the sport’s most thrilling storylines and taking women’s trick skiing to an entirely new level.

Image: Johnny Hayward

3. The Overall Saga

The men’s overall battle at the 2025 World Championships was the closest since 2009’s legendary three-way standoff, pitting Canada’s Dorien Llewellyn against defending champion Louis Duplan-Fribourg in a clash of precision, power, and pedigree.

The tournament began with a shock: Joel Poland, the sport’s most consistent tricker and early favorite, stumbled in the prelims. One front flip gone awry ended his flawless streak. Poland’s misstep became arguably the defining moment of the Worlds, a reminder that even the greatest can falter on the biggest stage.

From there, the men’s overall title came down to a hair. Duplan-Fribourg dominated tricks, setting the top score, and matched his personal best in slalom—but was penalized after a video gate review nullified his 10.75m pass, leaving him just 13 points behind Llewellyn. Every move counted.

Llewellyn, aiming to secure the title in the trick final, miscued on a landing and sank in disbelief, keeping the championship undecided. It all came down to jump. Duplan-Fribourg needed just 70 centimeters more to snatch the crown but came up short. In a performance echoing his 2021 duel with Joel Poland, Llewellyn soared 69.9 meters (229 feet), his best jump in years.

With that leap, Dorien Llewellyn followed in his father’s footsteps, claiming the World Overall title and cementing his place among water skiing royalty.

The 2025 World Championships proved that in overall competition, margins are measured in centimeters—and legends are defined by their ability to seize—or survive—the smallest of moments.

Image: Bret Ellis

2. Winter Returns; Cooler than Ever

If Hollywood scripted a comeback, could it have been as dramatic as Freddie Winter’s at the 2025 U.S. Masters? Less than a year after shattering his femur in Monaco and missing most of 2024, the two-time world slalom champion returned to Robin Lake with history, expectations, and personal demons stacked against him. Winter’s fraught relationship with the Masters added another layer: banned in 2023 after an emotionally charged judging dispute, he had unfinished business on the event’s storied waters.

When the dust settled on Saturday’s brutal semifinals, the veterans were gone, leaving Winter as one of the few household names in the final. Last off the dock, chasing a lead set by Nate Smith, he hurled himself outside of three ball with trademark fearlessness. When the spray settled, Winter had done it—his first professional victory since his injury, his third Masters title, and arguably the most satisfying of his career. “Probably the most emotional moment of my life,” he said afterward. “So much self-doubt and fear I wouldn’t get back here over the last 10 months and 29 days.”

The Masters wasn’t just a singular triumph. It set the tone for the rest of Winter’s season: a string of consistent performances that saw him claim the Waterski Pro Tour title, rack up four pro victories (tying Nate Smith), and lead the year-end podium count. Though perhaps not fully back at 100 percent, Winter had reclaimed his place among the sport’s elite, proving that even after a potentially career ending injury, he could still define the men’s slalom narrative.

At Robin Lake, Freddie Winter reminded the water skiing world: the best stories aren’t just about victories—they’re about the journey to get there.

Image: Johnny Hayward

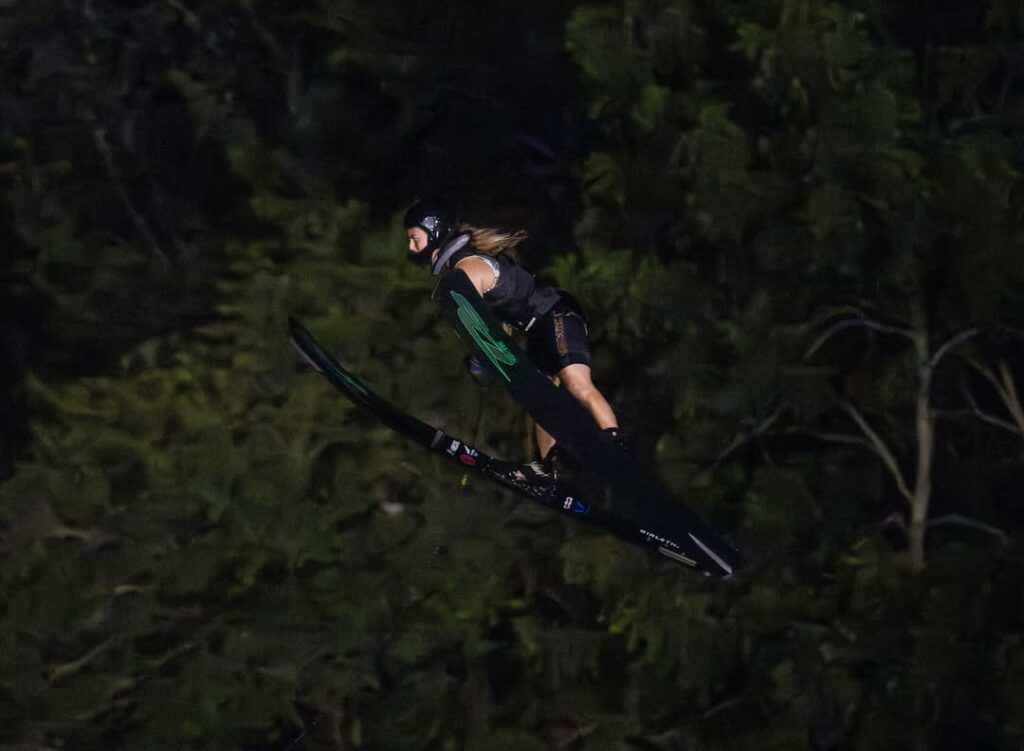

1. Jump Fest in Recetto

Across the sport, each new year seems to push performances to new and unprecedented heights. At many events, it has become commonplace for skiers to challenge—or even break—world records to clinch victory. It is, by almost any measure, a remarkable era to be a water ski fan.

One discipline, however, has largely resisted that trend. Jumping, with fewer events and shrinking opportunities, has seen its depth thin and top-end performances plateau. The concerning reality is that jump distances have not meaningfully improved this century and, by several metrics, have begun to decline.

All of which made what unfolded in Italy at this year’s World Championships all the more remarkable.

The tone was set in the opening days. Brandon Schipper arrived off a long-haul flight, skipped familiarization, and promptly unleashed the biggest jumps of his career. He wasn’t alone. Across the early rounds, season-bests and lifetime bests fell like dominoes. By week’s end, the cut to make the men’s jump final was the highest in World Championships history.

The finals delivered the crescendo. On the women’s side, personal bests stacked quickly—Maise Jacobsen and Aaliyah Yoong Hannifah both breaking 50 meters for the first time, with the entire top five clearing 170 feet. Brittany Greenwood Wharton, capping a career-best season, produced her longest jump in years to set the target. Hanna Straltsova, unflappable as ever, needed just two jumps to defend her title and complete another golden double.

Then came the men’s final—chaos, courage, and generational turnover wrapped into one shoreline spectacle. Eighteen-year-old Tim Wild, fresh off his first-ever 60-meter jump days earlier, flew 68.1m to announce himself on the sport’s biggest stage. Eight men cracked 220 feet. Schipper, giddy after another personal best, tapped home early, almost disbelieving what he’d just unleashed.

But the crown belonged to Joel Poland. His opening leap—72.1m, a personal best and new European record—froze the crowd. He passed his remaining jumps, gambling it would hold. It did. Ryan Dodd chased, cleared 70, and fell just short. With that, a three-decade lineage of North American jump dominance quietly ended.

In a discipline that had seemed stuck in neutral, Recetto felt like liftoff. Against every recent trend, jump delivered depth, drama, and distances that forced a recalibration of what was possible. Perhaps there is new life in water ski jumping after all.

Honorable Mentions

- Aaliyah Yoong Hannifah’s triple-gold performance at the University World Championships, the first world titles ever won by an Asian competitor.

- Tim Wild’s historic clean sweep at the Junior Masters—the first by a male skier in the event’s history.

- Hanna Straltsova breaking the longest-standing record in the sport, by less than a third of an overall point.

- Charlie Ross running 10.25m (41 off) at two different tournaments on the same day, breaking Will Asher’s 22-year-old collegiate record and tying for the lead at a professional event in the process.

- Joel Poland setting yet another world record in professional competition to clinch the WWS Overall Tour season title.